- Home

- Raymond Chandler

The Annotated Big Sleep Page 12

The Annotated Big Sleep Read online

Page 12

She was wearing a pair of long jade earrings. They were nice earrings and had probably cost a couple of hundred dollars. She wasn’t wearing anything else.7

She had a beautiful body, small, lithe, compact, firm, rounded. Her skin in the lamplight had the shimmering luster of a pearl. Her legs didn’t quite have the raffish grace of Mrs. Regan’s legs, but they were very nice.8 I looked her over without either embarrassment or ruttishness. As a naked girl she was not there in that room at all. She was just a dope. To me she was always just a dope.9

I stopped looking at her and looked at Geiger.10 He was on his back on the floor, beyond the fringe of the Chinese rug, in front of a thing that looked like a totem pole. It had a profile like an eagle and its wide round eye was a camera lens. The lens was aimed at the naked girl in the chair. There was a blackened flash bulb11 clipped to the side of the totem pole. Geiger was wearing Chinese slippers with thick felt soles, and his legs were in black satin pajamas and the upper part of him wore a Chinese embroidered coat, the front of which was mostly blood. His glass eye shone brightly up at me and was by far the most life-like thing about him. At a glance none of the three shots I heard had missed. He was very dead.

The flash bulb was the sheet lightning I had seen. The crazy scream was the doped and naked girl’s reaction to it. The three shots had been somebody else’s idea of how the proceedings might be given a new twist. The idea of the lad who had gone down the back steps and slammed into a car and raced away. I could see merit in his point of view.

A couple of fragile gold-veined glasses rested on a red lacquer tray on the end of the black desk, beside a pot-bellied flagon of brown liquid. I took the stopper out and sniffed at it. It smelled of ether and something else, possibly laudanum.12 I had never tried the mixture but it seemed to go pretty well with the Geiger menage.13

I listened to the rain hitting the roof and the north windows. Beyond was no other sound, no cars, no siren, just the rain beating. I went over to the divan and peeled off my trench coat and pawed through the girl’s clothes. There was a pale green rough wool dress of the pull-on type, with half sleeves. I thought I might be able to handle it. I decided to pass up her underclothes, not from feelings of delicacy, but because I couldn’t see myself putting her pants on and snapping her brassiere. I took the dress over to the teak chair on the dais. Miss Sternwood smelled of ether also, at a distance of several feet. The tinny chuckling noise was still coming from her and a little froth oozed down her chin. I slapped her face. She blinked and stopped chuckling. I slapped her again.

“Come on,” I said brightly. “Let’s be nice. Let’s get dressed.”

She peered at me, her slaty eyes as empty as holes in a mask. “Gugutoterell,”14 she said.

I slapped her around a little more. She didn’t mind the slaps.15 They didn’t bring her out of it. I set to work with the dress. She didn’t mind that either. She let me hold her arms up and she spread her fingers out wide, as if that was cute. I got her hands through the sleeves, pulled the dress down over her back, and stood her up. She fell into my arms giggling. I set her back in the chair and got her stockings and shoes on her.

“Let’s take a little walk,” I said. “Let’s take a nice little walk.”

We took a little walk.16 Part of the time her earrings banged against my chest and part of the time we did the splits in unison, like adagio dancers. We walked over to Geiger’s body and back. I had her look at him. She thought he was cute. She giggled and tried to tell me so, but she just bubbled. I walked her over to the divan and spread her out on it. She hiccuped twice, giggled a little and went to sleep. I stuffed her belongings into my pockets and went over behind the totem pole thing. The camera17 was there all right, set inside it, but there was no plateholder in the camera. I looked around on the floor, thinking he might have got it out before he was shot. No plateholder. I took hold of his limp chilling hand and rolled him a little. No plateholder. I didn’t like this development.

I went into a hall at the back of the room and investigated the house. There was a bathroom on the right and a locked door, a kitchen at the back. The kitchen window had been jimmied.18 The screen was gone and the place where the hook had pulled out showed on the sill. The back door was unlocked. I left it unlocked and looked into a bedroom on the left side of the hall. It was neat, fussy, womanish. The bed had a flounced cover.19 There was perfume on the triple-mirrored dressing table, beside a handkerchief, some loose money, a man’s brushes, a keyholder. A man’s clothes were in the closet and a man’s slippers under the flounced edge of the bed cover. Mr. Geiger’s room. I took the keyholder back to the living room and went through the desk. There was a locked steel box in the deep drawer. I used one of the keys on it. There was nothing in it but a blue leather book with an index and a lot of writing in code, in the same slanting printing that had written to General Sternwood. I put the notebook in my pocket, wiped the steel box where I had touched it, locked the desk up, pocketed the keys, turned the gas logs off in the fireplace, wrapped myself in my coat and tried to rouse Miss Sternwood. It couldn’t be done. I crammed her vagabond hat on her head and swathed her in her coat and carried her out to her car. I went back and put all the lights out and shut the front door, dug her keys out of her bag and started the Packard. We went off down the hill without lights. It was less than ten minutes’ drive to Alta Brea Crescent. Carmen spent them snoring and breathing ether in my face. I couldn’t keep her head off my shoulder. It was all I could do to keep it out of my lap.20

1. Chandler scholar Philip Durham notes that this scene exemplifies the objective “camera eye” narrative made famous by Hammett and Hemingway. Marlowe’s eye pans around the room, neutrally registering and cataloging all it sees, from lamp to desk to naked girl to corpse. Black Mask editor Joseph Shaw extolled this style, and Chandler worked hard to master it: “I am committed as a writer to a point of view,” he writes; “namely, that the possibilities of objective writing are very great and they have scarcely been explored.” Chandler’s early third-person stories hew most closely to the objective ideal; his first-person stories, starting with “Finger Man” (1934), begin to blend in the subjective impressions of a distinct sensibility. That sensibility becomes definitively Marlowe’s in The Big Sleep.

2. In all the scenes in which Geiger is mentioned he is either absent, seen at a distance, or dead. Here his character is neatly conveyed through Marlowe’s inventory of his living room: luxurious, over-decorated, and dripping with Orientalism (the exoticizing of Eastern culture and artifacts). Geiger’s tastes would code him as gay for attentive readers of the time (an identity that will be made explicit). Marlowe’s distaste pervades the apparent neutrality of his description.

Chandler takes a page from Hammett’s book in his depiction of Geiger. Hammett was probably the first to depict gay characters and relationships in a crime novel, with The Maltese Falcon’s queer trio, Casper Gutman, Joel Cairo, and Wilmer Cook—at least, he thought he was the first. His editor at Black Mask had eliminated suggestions of homosexuality from the magazine version (see note 9 on this page). When Hammett’s editor at Knopf objected to them as well, he wrote back, “I should like to have them as they are, especially since you say they would be all right perhaps in an ordinary novel. It seems to me that the only thing that can be said against their use in a detective novel is that nobody has tried it yet. I’d like to try it.”

3. In The Little Sister, Marlowe describes a high-pitched sound as “like a couple of pansies fighting over a piece of silk.” Typically for a hard-boiled dick, Marlowe dislikes effeminate men, regardless of their sexual orientation. In Farewell, My Lovely, he refers to wealthy playboy Lindsay Marriott as a “pansy” despite typing him as “a lad who would have a lot of lady friends.” It is Marriott’s money, manners, and tastes that earn him the slur, rather than his sexuality.

4. cordite: A smokeless explosive used mostly in ammunition. The scent of cordite wo

uld indicate that a shot has been fired.

5. Ether became a common anesthetic and recreational drug in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

6. Teakwood is native to Myanmar and the Philippines, so the chair fits right into Geiger’s hodgepodge of “exotic” Eastern trappings.

7. This was a tricky scene for Howard Hawks to film in the 1940s. The Motion Picture Production Code, known as the Hays Code (the forerunner of the present rating system, named after the president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America), established a strict set of rules defining acceptable moral content in films beginning in the 1930s. Hawks was forced to film a fully clothed Martha Vickers.

Martha Vickers as Carmen, clothed (Photofest)

“SHE WAS STARK NAKED”: FROM “KILLER IN THE RAIN”

The opening of Chapter Seven has its corollary in the 1935 short story.

That room reached all the way across the front of the house and had a low, beamed ceiling, walls painted brown. Strips of tapestry hung all around the walls. Books filled low shelves. There was a thick, pinkish rug on which some light fell from two standing lamps with pale green shades. In the middle of the rug there was a big, low desk and a black chair with a yellow satin cushion at it. There were books all over the desk.

On a sort of dais near one end wall there was a teakwood chair with arms and a high back. A dark-haired girl was sitting in the chair, on a fringed red shawl.

She sat very straight, with her hands on the arms of the chair, her knees close together, her body stiffly erect, her chin level. Her eyes were wide open and mad and had no pupils.

She looked unconscious of what was going on, but she didn’t have the pose of unconsciousness. She had a pose as if she was doing something very important and making a lot of it.

Out of her mouth came a tinny chuckling noise, which didn’t change her expression or move her lips. She didn’t seem to see me at all.

She was wearing a pair of long jade earrings, and apart from those she was stark naked.

8. Scenes like this one led renowned literary critic Leslie Fiedler, in his touchstone Love and Death in the American Novel, to accuse Chandler of resorting to “populist semi-pornography.” Although Marlowe behaves with nothing but professionalism—if not gallantry—here, this scene with the drugged-up naked girl must have offered a frisson of titillation to Chandler’s readers. Of course, the difference between The Big Sleep’s readers and, say, purchasers of Geiger’s books is that Chandler arouses the sexual impulse only to have Marlowe repudiate it. And, of course, The Big Sleep didn’t come with pictures. Some of its lurid mass market paperback covers did their best to re-create that titillation, however!

The drugged and naked “luscious mantrap” about to be struck (Pocket Books, 1950/Simon & Schuster, cover art by Harvey Kidder)

9. The sense of “dope” as foolish or stupid derives from its earlier sense as an opiate or other narcotic mixture. Marlowe plays on both senses in this scene. In The Dain Curse, the Continental Op finds Gabrielle Dain Leggett doped up and half undressed in the temple of a local cult. “Her face was white as lime. Her eyes were all brown, dull, focused on nothing, and her small forehead was wrinkled. She looked as if she knew there was something in front of her and was wondering what it was.”

10. Geiger appears as Steiner in “Killer in the Rain,” with similarly effeminate tastes: he wears a green leather jacket and carries a fancy cigarette holder. Detective Carmady doesn’t comment on this in the story, however, and there is no further suggestion that Steiner, who turns out to be involved in an affair with Carmen Dravec, is gay.

11. The flashbulb came into popular usage in the late 1920s, replacing flash powder.

12. laudanum: An alcoholic herbal preparation containing approximately 10 percent powdered opium. A drug that was favored by the Romantics and widely used in the Victorian era. Famous literary users include Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Thomas De Quincey, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Wilkie Collins. By the 1930s laudanum was available over the counter at drugstores, and mixing it with other drugs such as ether or hashish was a common practice.

13. As a drug of Eastern origin, it goes with the Oriental trappings, a link that was already well established when Chandler was writing.

14. “G-g-go-ta-hell” is the equivalent line in “Killer in the Rain.”

15. Nor does Marlowe seem to. Chandler dropped “not very hard” from the original scene in “Killer in the Rain” and adds the significant preposition “around.” The first two slaps might have been for her own good, but medical practitioners, for example, do not slap patients “around” to bring them to.

American culture at large did not object to representations of violence against women before the women’s rights movement of the 1960s and ’70s. In the hard-boiled and noir genres generally, women were routinely knocked around by male characters to signify the masculine virtues of strength and toughness. The next generation’s Mickey Spillane took it to ridiculous extremes in his Mike Hammer novels. Critic Erin A. Smith has discussed Chandler’s era as one in which masculinity was under threat, leading to hard-boiled as an über-macho retort to that threat. A scene from James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice from 1934: “I hauled off and hit her in the eye as hard as I could. She went down. She was right down there at my feet, her eyes shining, her breasts trembling, drawn up in tight points, and pointing right back at me.” This is so egregious that we might feel relief while watching the same year’s Academy Award–sweeping It Happened One Night, in which Clark Gable raises a hand to strike Claudette Colbert, twice, with no objection or concern from the multiple onlookers. At least in this lovely romantic comedy he was only pretending. See the 1950 Pocket Books cover, on this page, for Marlowe in the pose.

16. Sam Spade takes a doped-up Rhea Gutman for a similar walk in The Maltese Falcon: “Spade made her walk….One of his arms around her small body, that hand under her armpit, his other hand gripping her other arm, held her erect when she stumbled, checked her swaying, kept urging her forward, but made her tottering legs bear all her weight they could bear. They walked across and across the floor, the girl falteringly, with incoordinate steps, Spade surely on the balls of his feet with balance unaffected by her staggering.”

17. The camera isn’t identified. One likely model would be a Graflex Speed Graphic, the type used by the photojournalist known as Weegee, who used it to capture the lurid and violent images of 1945’s Naked City. In cameras of this type film was loaded into a separate apparatus, or plateholder, that held cut sheets of film.

Graflex Speed Graphic

18. jimmied: To jimmy is to force open a window or door, from the thieves’ slang for a burglar’s crowbar, a jimmy.

19. flounced cover: A flounce is a strip of pleated material attached to clothing or a bedspread as a decorative frill. “To flounce” also means to move with exaggerated emotion. According to Farmer and Henley’s Dictionary of Slang and Colloquial English (1905), it was originally “said of women, for whom such a motion is, or rather was, inseparable from a great flourishing of flounces.” Steiner’s bed in “Killer in the Rain” also has a flounced spread.

20. (Ahem.) So far Marlowe has effortlessly played the gentleman, but his suppressed sexual instincts will return with a vengeance in Chapter Twenty-Four.

EIGHT

There was dim light behind narrow leaded panes in the side door of the Sternwood mansion. I stopped the Packard under the porte-cochere1 and emptied my pockets out on the seat. The girl snored in the corner, her hat tilted rakishly over her nose, her hands hanging limp in the folds of the raincoat. I got out and rang the bell. Steps came slowly, as if from a long dreary distance. The door opened and the straight, silvery butler looked out at me. The light from the hall made a halo of his hair.

He sa

id: “Good evening, sir,” politely and looked past me at the Packard. His eyes came back to look at my eyes.

“Is Mrs. Regan in?”

“No, sir.”

“The General is asleep, I hope?”

“Yes. The evening is his best time for sleeping.”

“How about Mrs. Regan’s maid?”

“Mathilda? She’s here, sir.”

“Better get her down here. The job needs the woman’s touch. Take a look in the car and you’ll see why.”

He took a look in the car. He came back. “I see,” he said. “I’ll get Mathilda.”

“Mathilda will do right by her,” I said.

“We all try to do right by her,” he said.

“I guess you have had practice,” I said.

He let that one go. “Well, good-night,” I said. “I’m leaving it in your hands.”

“Very good, sir. May I call you a cab?”

“Positively,” I said, “not. As a matter of fact I’m not here. You’re just seeing things.”

He smiled then. He gave me a duck of his head and I turned and walked down the driveway and out of the gates.

Ten blocks of that,2 winding down curved rain-swept streets, under the steady drip of trees, past lighted windows in big houses in ghostly enormous grounds, vague clusters of eaves and gables and lighted windows high on the hillside, remote and inaccessible, like witch houses in a forest.3 I came out at a service station glaring with wasted light, where a bored attendant in a white cap and a dark blue windbreaker sat hunched on a stool, inside the steamed glass, reading a paper. I started in, then kept going. I was as wet as I could get already. And on a night like that you can grow a beard waiting for a taxi. And taxi drivers remember.

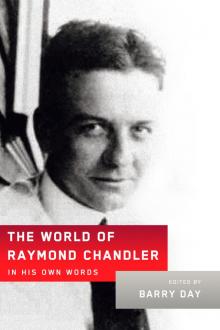

The World of Raymond Chandler: In His Own Words

The World of Raymond Chandler: In His Own Words Red Wind: A Collection of Short Stories

Red Wind: A Collection of Short Stories The Big Sleep

The Big Sleep Killer in the Rain

Killer in the Rain Playback

Playback The Simple Art of Murder

The Simple Art of Murder The Bronze Door

The Bronze Door The Little Sister

The Little Sister The Lady in the Lake

The Lady in the Lake The Annotated Big Sleep

The Annotated Big Sleep The Collected Raymond Chandler

The Collected Raymond Chandler Collected Stories (Everyman's Library)

Collected Stories (Everyman's Library) Farewell, My Lovely

Farewell, My Lovely Trouble Is My Business

Trouble Is My Business The Long Goodbye

The Long Goodbye The Lady in the Lake pm-4

The Lady in the Lake pm-4 The Big Sleep pm-1

The Big Sleep pm-1 The World of Raymond Chandler

The World of Raymond Chandler Collected Stories of Raymond Chandler

Collected Stories of Raymond Chandler Red Wind

Red Wind Farewell, My Lovely pm-2

Farewell, My Lovely pm-2 The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Nonfiction, 1909–1959

The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Nonfiction, 1909–1959 Playback pm-7

Playback pm-7 The High Window pm-3

The High Window pm-3 The Little Sister pm-5

The Little Sister pm-5 Poodle Springs (philip marlowe)

Poodle Springs (philip marlowe) The Long Goodbye pm-6

The Long Goodbye pm-6