- Home

- Raymond Chandler

Red Wind Page 11

Red Wind Read online

Page 11

Mardonne said: “I’m not busy any more, Henry.”

The blond boy shut the door. Mallory stood up and backed slowly towards the wall. He said grimly:

“Now for the funny stuff, eh?”

Mardonne put brown fingers up and pinched the fat part of his chin. He said curtly:

“There won’t be any shooting here. Nice people come to this house. Maybe you didn’t spot Landrey, but I don’t want you around. You’re in my way.”

Mallory kept on backing until he had his shoulders against the wall. The blond boy frowned, took a step towards him. Mallory said:

“Stay right where you are, Henry. I need room to think. You might get a slug into me, but you wouldn’t stop my gun from talking a little. The noise wouldn’t bother me at all.”

Mardonne bent over his desk, looking sidewise. The blond boy slowed up. His tongue still peeped out between his lips. Mardonne said:

“I’ve got some C notes in the desk here. I’m giving Henry ten of them. He’ll go to your hotel with you. He’ll even help you pack. When you get on the train East he’ll pass you the dough. If you come back after that, it will be a new deal—from a cold deck.” He put his hand down slowly and opened the desk drawer.

Mallory kept his eyes on the blond boy. “Henry might make a change in the continuity,” he said unpleasantly. “Henry looks kind of unstable to me.”

Mardonne stood up, brought his hand from the drawer. He dropped a packet of notes on top of the desk. He said:

“I don’t think so. Henry usually does what he is told.”

Mallory grinned tightly. “Perhaps that’s what I’m afraid of,” he said. His grin got tighter still, and crookeder. His teeth glittered between his pale lips. “You said you thought a lot of Landrey, Mardonne. That’s hooey. You don’t care a thin dime about Landrey, now he’s dead. You probably stepped right into his half of the joint, and nobody around to ask questions. It’s like that in the rackets. You want me out because you think you can still peddle your dirt—in the right place—for more than this small time joint would net in a year. But you can’t peddle it, Mardonne. The market’s closed. Nobody’s going to pay you a plugged nickel either to spill it or not to spill it.”

Mardonne cleared his throat softly. He was standing in the same position, leaning forward a little over the desk, both hands on top of it, and the packet of notes between his hands. He licked his lips, said:

“All right, master mind. Why not?”

Mallory made a quick but expressive gesture with his right thumb.

“I’m the sucker in this deal. You’re the smart guy. I told you a straight story the first time and my hunch says Landrey wasn’t in that sweet frame alone. You were in it up to your fat neck!… But you aced yourself backwards when you let Landrey pack those letters around with him. The girl can talk now. Not a whole lot, but enough to get backing from an outfit that isn’t going to scrap a million-dollar reputation because some cheap gambler wants to get smart… If your money says different, you’re going to get a jolt that’ll have you picking your eyeteeth out of your socks. You’re going to see the sweetest cover-up even Hollywood ever fixed.”

He paused, flashed a quick glance at the blond boy. “Something else, Mardonne. When you figure on gun play get yourself a loogan that knows what it’s all about. The gay caballero here forgot to thumb back his safety.”

Mardonne stood frozen. The blond boy’s eyes flinched down to his gun for a split second of time. Mallory jumped fast along the wall, and his Luger snapped into his hand. The blond boy’s face tensed, his gun crashed. Then the Luger cracked, and a slug went into the wall beside the blond boy’s gay felt hat. Henry faded down gracefully, squeezed lead again. The shot knocked Mallory back against the wall. His left arm went dead.

His lips writhed angrily. He steadied himself; the Luger talked twice, very rapidly.

The blond boy’s gun arm jerked up and the gun sailed against the wall high up. His eyes widened, his mouth came open in a yell of pain. Then he whirled, wrenched the door open and pitched straight out on the landing with a crash.

Light from the room streamed after him. Somebody shouted somewhere. A door banged. Mallory looked at Mardonne, saying evenly:

“Got me in the arm, — ! I could have killed the — four times!”

Mardonne’s hand came up from the desk with a blued revolver in it. A bullet splashed into the floor at Mallory’s feet. Mardonne lurched drunkenly, threw the gun away like something red hot. His hands groped high in the air. He looked scared stiff.

Mallory said: “Get in front of me, big shot! I’m moving out of here.”

Mardonne came out from behind the desk. He moved jerkily, like a marionette. His eyes were as dead as stale oysters. Saliva drooled down his chin.

Something loomed in the doorway. Mallory heaved side-wise, firing blindly at the door. But the sound of the Luger was overborne by the terrific flat booming of a shotgun. Searing flame stabbed down Mallory’s right side. Mardonne got the rest of the load.

He plunged to the floor on his face, dead before he landed.

A sawed-off shotgun dumped itself in through the open door. A thick-bellied man in shirtsleeves eased himself down in the door-frame, clutching and rolling as he fell. A strangled sob came out of his mouth, and blood spread on the pleated front of a dress shirt.

Sudden noise flared out down below. Shouting, running feet, a shrilling off-key laugh, a high sound that might have been a shriek. Cars started outside, tires screeched on the driveway. The customers were getting away. A pane of glass went out somewhere. There was a loose clatter of running feet on a sidewalk.

Across the lighted patch of landing nothing moved. The blond boy groaned softly, out there on the floor, behind the dead man in the doorway.

Mallory plowed across the room, sank into the chair at the end of the desk. He wiped sweat from his eyes with the heel of his gun hand. He leaned his ribs against the desk, panting, watching the door.

His left arm was throbbing now, and his right leg felt like the plagues of Egypt. Blood ran down his sleeve inside, down on his hand, off the tips of two fingers.

After a while he looked away from the door, at the packet of notes lying on the desk under the lamp. Reaching across he pushed them into the open drawer with the muzzle of the Luger. Grinning with pain he leaned far enough over to pull the drawer shut. Then he opened and closed his eyes quickly, several times, squeezing them tight together, then snapping them open wide. That cleared his head a little. He drew the telephone towards him.

There was silence below stairs now. Mallory put the Luger down, lifted the phone off the prongs and put it down beside the Luger.

He said out loud: “Too bad, baby… Maybe I played it wrong after all… Maybe the louse hadn’t the guts to hurt you at that… well… there’s got to be talking done now.”

As he began to dial, the wail of a siren got louder coming up the long hill from Sherman…

X

THE uniformed officer behind the typewriter desk talked into a dictaphone, then looked at Mallory and jerked his thumb towards a glass-paneled door that said: “Captain of Detectives. Private.”

Mallory got up stiffly from a hard chair and went across the room, leaned against the wall to open the glass-paneled door, went on in.

The room he went into was paved with dirty brown linoleum, furnished with the peculiar sordid hideousness only municipalities can achieve. Cathcart, the captain of detectives, sat in the middle of it alone, between a littered roll-top desk that was not less than twenty years old and a flat oak table large enough to play ping-pong on.

Cathcart was a big shabby Irishman with a sweaty face and a loose-lipped grin. His white mustache was stained in the middle by nicotine. His hands had a lot of warts on them.

Mallory went towards him slowly, leaning on a heavy cane with a rubber tip. His right leg felt large and hot. His left arm was in a sling made from a black silk scarf. He was freshly shaved. His face was pale and his eyes w

ere as dark as slate.

He sat down across the table from the captain of detectives, put his cane on the table, tapped a cigarette and lit it. Then he said casually:

“What’s the verdict, chief?”

Cathcart grinned. “How you feel, kid? You look kinda pulled down.”

“Not bad. A bit stiff.”

Cathcart nodded, cleared his throat, fumbled unnecessarily with some papers that were in front of him. He said:

“You’re clear. It’s a lulu, but you’re clear. Chicago gives you a clean sheet—damn’ clean. Your Luger got Mike Corliss, a two-time loser. I’m keepin’ the Luger for a souvenir. Okey?”

Mallory nodded, said: “Okey. I’m getting me a .25 with copper slugs. A sharpshooter’s gun. No shock effect, but it goes better with evening clothes.”

Cathcart looked at him closely for a minute, then went on: “Mike’s prints are on the shotgun. The shotgun got Mardonne. Nobody’s cryin’ about that much. The blond kid ain’t hurt bad. That automatic we found on the floor had his prints and that will take care of him for a while.”

Mallory rubbed his chin slowly, wearily. “How about the others?”

The captain raised tangled eyebrows, and his eyes looked absent. He said: “I don’t know of nothin’ to connect you there. Do you?”

“Not a thing,” Mallory said apologetically. “I was just wondering.”

The captain said firmly: “Don’t wonder. And don’t get to guessin’, if anybody should ask you… Take that Baldwin Hills thing. The way we figure it Macdonald got killed in the line of duty, takin’ with him a dope-peddler named Slippy Morgan. We have a tag out for Slippy’s wife, but I don’t guess we’ll make her. Mac wasn’t on the narcotic detail, but it was his night off and he was a great guy to gumshoe around on his night off. Mac loved his work.”

Mallory smiled faintly, said politely: “Is that so?”

“Yeah,” the captain said. “In the other one it seems this Landrey, a known gambler—he was Mardonne’s partner too. That’s kind of a funny coincidence—went down to Westwood to collect dough from a guy called Costello that ran a book on the Eastern tracks. Jim Ralston, one of our boys, went with him. Hadn’t ought to, but he knew Landrey pretty well. There was a little trouble about the money. Jim got beaned with a blackjack and Landrey and some little hood fogged each other. There was another guy there we don’t trace. We got Costello, but he won’t talk and we don’t like to beat up an old guy. He’s got a rap comin’ on account of the blackjack. He’ll plead, I guess.”

Mallory slumped down in his chair until the back of his neck rested on top of it. He blew smoke straight up towards the stained ceiling. He said:

“How about night before last? Or was that the time the roulette wheel backfired and the trick cigar blew a hole in the garage floor?”

The captain of detectives rubbed both his moist cheeks briskly, then hauled out a very large handkerchief and snorted into it.

“Oh that,” he said negligently, “that wasn’t nothin’. The blond kid—Henry Anson or something like that—says it was all his fault. He was Mardonne’s bodyguard, but that didn’t mean he could go shootin’ anyone he might want to. That takes care of him, but we let him down easy for tellin’ a straight story.”

The captain stopped short and stared at Mallory hard-eyed. Mallory was grinning. “Of course if you don’t like his story…” the captain went on coldly.

Mallory said: “I haven’t heard it yet. I’m sure I’ll like it fine.”

“Okey,” Cathcart rumbled, mollified. “Well, this Anson says Mardonne buzzed him in where you and the boss were talkin’. You was makin’ a kick about something, maybe a crooked wheel downstairs. There was some money on the desk and Anson got the idea it was a shake. You looked pretty fast to him, and not knowing you was a dick he gets kinda nervous. His gun went off. You didn’t shoot right away, but the poor sap lets off another round and plugs you. Then, by — you drilled him in the shoulder, as who wouldn’t, only if it had been me, I’d of pumped his guts. Then the shotgun boy comes bargin’ in, lets go without asking any questions, fogs Mardonne and stops one from you. We kinda thought at first the guy might of got Mardonne on purpose, but the kid says no, he tripped in the door comin’ in… Hell, we don’t like for you to do all that shooting, you being a stranger and all that, but a man ought to have a right to protect himself against illegal weapons.”

Mallory said gently: “There’s the D.A. and the coroner. How about them? I’d kind of like to go back as clean as I came away.”

Cathcart frowned down at the dirty linoleum and bit his thumb as if he liked hurting himself.

“The coroner don’t give a damn about that trash. If the D.A. wants to get funny, I can tell him about a few cases his office didn’t clean up so good.”

Mallory lifted his cane off the table, pushed his chair back, put weight on the cane and stood up. “You have a swell police department here,” he said. “I shouldn’t think you’d have any crime at all.”

He moved across towards the outer door. The captain said to his back:

“Goin’ on to Chicago?”

Mallory shrugged carefully with his right shoulder, the good one. “I might stick around,” he said. “One of the studios made me a proposition. Private extortion detail. Blackmail and so on.”

The captain grinned heartily. “Swell,” he said. “Eclipse Films is a swell outfit. They always been swell to me… Nice easy work, blackmail. Oughtn’t to run into any rough stuff.”

Mallory nodded solemnly. “Just light work, Chief. Almost effeminate, if you know what I mean.”

He went on out, down the hall to the elevator, down to the street. He got into a taxi. It was hot in the taxi. He felt faint and dizzy going back to his hotel.

I’LL BE WAITING

AT ONE o’clock in the morning, Carl, the night porter, turned down the last of three table lamps in the main lobby of the Windermere Hotel. The blue carpet darkened a shade or two and the walls drew back into remoteness. The chairs filled with shadowy loungers. In the corners were memories like cobwebs.

Tony Reseck yawned. He put his head on one side and listened to the frail, twittery music from the radio room beyond a dim arch at the far side of the lobby. He frowned. That should be his radio room after one A.M. Nobody should be in it. That red-haired girl was spoiling his nights.

The frown passed and a miniature of a smile quirked at the corners of his lips. He sat relaxed, a short, pale, paunchy, middle-aged man with long, delicate fingers clasped on the elk’s tooth on his watch chain; the long delicate fingers of a sleight-of-hand artist, fingers with shiny, molded nails and tapering first joints, fingers a little spatulate at the ends. Handsome fingers. Tony Reseck rubbed them gently together and there was peace in his quiet sea-gray eyes.

The frown came back on his face. The music annoyed him. He got up with a curious litheness, all in one piece, without moving his clasped hands from the watch chain. At one moment he was leaning back relaxed, and the next he was standing balanced on his feet, perfectly still, so that the movement of rising seemed to be a thing imperfectly perceived, an error of vision…

He walked with small, polished shoes delicately across the blue carpet and under the arch. The music was louder. It contained the hot, acid blare, the frenetic, jittering runs of a jam session. It was too loud. The red-haired girl sat there and stared silently at the fretted part of the big radio cabinet as though she could see the band with its fixed professional grin and the sweat running down its back. She was curled up with her feet under her on a davenport which seemed to contain most of the cushions in the room. She was tucked among them carefully, like a corsage in the florist’s tissue paper.

She didn’t turn her head. She leaned there, one hand in a small fist on her peach-colored knee. She was wearing lounging pajamas of heavy ribbed silk embroidered with black lotus buds.

“You like Goodman, Miss Cressy?” Tony Reseck asked.

The girl moved her eyes slowly. The light

in there was dim, but the violet of her eyes almost hurt. They were large, deep eyes without a trace of thought in them. Her face was classical and without expression.

She said nothing.

Tony smiled and moved his fingers at his sides, one by one, feeling them move. “You like Goodman, Miss Cressy?” he repeated gently.

“Not to cry over,” the girl said tonelessly.

Tony rocked back on his heels and looked at her eyes. Large, deep, empty eyes. Or were they? He reached down and muted the radio.

“Don’t get me wrong,” the girl said. “Goodman makes money, and a lad that makes legitimate money these days is a lad you have to respect. But this jitterbug music gives me the backdrop of a beer flat. I like something with roses in it.”

“Maybe you like Mozart,” Tony said.

“Go on, kid me,” the girl said.

“I wasn’t kidding you, Miss Cressy. I think Mozart was the greatest man that ever lived—and Toscanini is his prophet.”

“I thought you were the house dick.” She put her head back on a pillow and stared at him through her lashes.

“Make me some of that Mozart,” she added.

“It’s too late,” Tony sighed. “You can’t get it now.”

She gave him another long lucid glance. “Got the eye on me, haven’t you, flatfoot?” She laughed a little, almost under her breath. “What did I do wrong?”

Tony smiled his toy smile. “Nothing, Miss Cressy. Nothing at all. But you need some fresh air. You’ve been five days in this hotel and you haven’t been outdoors. And you have a tower room.”

She laughed again. “Make me a story about it. I’m bored.”

“There was a girl here once had your suite. She stayed in the hotel a whole week, like you. Without going out at all, I mean. She didn’t speak to anybody hardly. What do you think she did then?”

The girl eyed him gravely. “She jumped her bill.”

He put his long delicate hand out and turned it slowly, fluttering the fingers, with an effect almost like a lazy wave breaking. “Unh-uh. She sent down for her bill and paid it. Then she told the hop to be back in half an hour for her suitcases. Then she went out on her balcony.”

The World of Raymond Chandler: In His Own Words

The World of Raymond Chandler: In His Own Words Red Wind: A Collection of Short Stories

Red Wind: A Collection of Short Stories The Big Sleep

The Big Sleep Killer in the Rain

Killer in the Rain Playback

Playback The Simple Art of Murder

The Simple Art of Murder The Bronze Door

The Bronze Door The Little Sister

The Little Sister The Lady in the Lake

The Lady in the Lake The Annotated Big Sleep

The Annotated Big Sleep The Collected Raymond Chandler

The Collected Raymond Chandler Collected Stories (Everyman's Library)

Collected Stories (Everyman's Library) Farewell, My Lovely

Farewell, My Lovely Trouble Is My Business

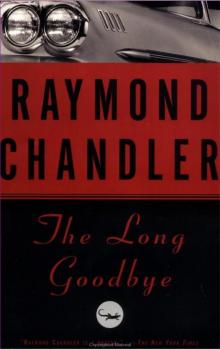

Trouble Is My Business The Long Goodbye

The Long Goodbye The Lady in the Lake pm-4

The Lady in the Lake pm-4 The Big Sleep pm-1

The Big Sleep pm-1 The World of Raymond Chandler

The World of Raymond Chandler Collected Stories of Raymond Chandler

Collected Stories of Raymond Chandler Red Wind

Red Wind Farewell, My Lovely pm-2

Farewell, My Lovely pm-2 The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Nonfiction, 1909–1959

The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Nonfiction, 1909–1959 Playback pm-7

Playback pm-7 The High Window pm-3

The High Window pm-3 The Little Sister pm-5

The Little Sister pm-5 Poodle Springs (philip marlowe)

Poodle Springs (philip marlowe) The Long Goodbye pm-6

The Long Goodbye pm-6